By 1998, more than 50,000 Irish women had their children taken away from them in Mother-and-Baby-Homes. Being pregnant and unmarried was considered an unforgivable disgrace in arch-Catholic Ireland – and the Church was so powerful that it alone decided the future of the babies. An independent commission was supposed to provide clarification in 2021, but the report is considered incomplete and full of gaps.

By Mareike Graepel, Dublin

In Ireland, contraception and abortion were long prohibited, sex before marriage was not allowed, sex education practically non-existent. In the case of unplanned pregnancies, the woman was considered the “culprit” for her “condition” – regardless of whether the baby was by her boyfriend, conceived in a relationship of dependency, or if it was the result of rape or abuse. Those who did not want to, or could not go abroad to terminate the pregnancy illegally, had no choice in the fabric of the Irish family determined by Church and tradition: The priest was informed. He decided whether the women were to be abandoned or taken to one of the 18 Catholic Mother-and-Baby-Homes.

In the Hollywood film “Philomena”, Judi Dench plays a woman who only managed at an advanced age to find out details about her son, whom she gave birth to in 1951 in the Sean Ross Abbey Mother-and-Baby-Home. He had been sold to America against her will – for the equivalent of 910 Euro. He had travelled to Ireland three times as an adult in vain to find his mother. When Philomena Lee finally located him in 2003, it was too late. He had already died in 1995.

Women could not just leave

What sounds like fiction is a shocking reality: Between 1922 and 1998, 56,000 unmarried Irish mothers gave birth to children who were taken away from them after birth. Philomena Lee was one of them. Currently, she and eight other women have been able to sue in the Irish Supreme Court to have parts of the Mother and Baby Home Report, published in 2021, declared invalid.

The background: The report was incomplete, wrong in many places and claimed that the women were not “locked up” in the strict sense of the word and could have left at any time. Philomena Lee, however, had put on record for the report, among other things, that girls who tried to run away were brought back by the Gardaí, the Irish police. A good ten years before the report, a gruesome discovery had set the investigation into Mother-and-Baby-Homes in motion in the first place.

In the small town of Tuam in the west of Ireland, amateur historian Catherine Corless discovered that the bodies of almost 800 children lie in an unregistered mass grave in the home there. Many were dumped like rubbish, thrown into an old septic tank. But the dead babies of Tuam were only the tip of the iceberg. It is estimated that by 1960 alone more than 6,000 babies had died in Ireland’s Mother-and-Baby-Homes. Exact figures are not available. But the Irish Government had to react and it commissioned an independent enquiry.

64-year-old Maggie Corbett had two daughters in the Bessborough Mother-and-Baby-Home in Cork. She says she remembers it like it was yesterday. “I had to get up after the birth and scrub the table and floor in the otherwise empty room where I had just delivered my baby. Before that, we were left alone for hours until we were dilating enough.” During bearing-down contractions, the nuns would have sat on her chest and screamed in her face: “This pain is your own fault, you dirty bitch, this is for your sins.”

The petite woman with the blond hair says that like the other unmarried pregnant women in the home, she had to work hard and lived in small dormitories without running water. She had not been there voluntarily either time: Nuns came to pick her up at home, took away her just a few weeks old babies and gave them up for adoption against her will. “We didn’t have to be ordered to keep quiet about all that, at all. We were so ashamed, we believed what they told us about ourselves.” To this day, she has not talked about it with her mother, nor with her friends or siblings.

The second time she knew what to expect

“I was the oldest of twelve children, and although my mother was heartbroken that I was taken, she did nothing. My father and the priest made it unmistakably clear: I have brought shame on all of us, on the family and on the town.” And the children’s fathers? She says they wanted nothing to do with it, neither in 1976 nor in 1978.

One was protected by his family and made her out to be “easy”. “Yet I had no idea what had happened to me. I didn’t know I could get pregnant.” The other took advantage of the fact that she was vulnerable and in search of closeness and affection after the first pregnancy and because she was longing for her child; she drank too much because of – as she now knows – postnatal depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and trusted him blindly. She became pregnant again. She was on her own again. She was taken to Bessborough, alone again. Only this time she knew what to expect.

Maggie Corbett speaks calmly, only rarely becoming agitated, she smiles a lot as she tells her story. She is proud of her courage to be open and a little bit proud of having survived so much hardship. She has brought photos for the meeting. Some of them make her cry. She shows pictures of her first daughter, Joanne, whom she had actually named Martina-Samantha. “I only saw her again when she was already a mother and I was a grandmother.” And she shows a child’s photo of the second girl, whom she has not yet been able to find. She is sure that Marie-Antoinette is alive, she feels it, but she surely bears another name.

The mothers were also renamed by the nuns. Maggie became “Olga” when she first arrived at Bessborough, three months pregnant – and likewise when she was there again two years later. “With the second baby they didn’t wake me up at night, they didn’t tell me until the next morning that my little one was gone.” Probably because they worried she would try to stop it. “When they took my first child, the nuns stood by my bed at one o’clock in the morning and said: ‘Wake up, Olga, your child is gone now: Forever.’ I often couldn’t sleep when the next baby was born.” And yet she could not prevent her second daughter from being snatched away from her.

“When I tried to confront the nun who ran Bessborough in 1990 to get help in finding my children, she said, ‘Oh, come on, we weren’t that bad, were we?’ All I could do was stare at her and say nothing more.” It was to be another 16 years before she was able to meet her first daughter again – thanks to support by a social worker.

After two failed marriages, another daughter named Ríona, and a degree in social sciences when she was already in her mid-40s, Maggie Corbett can say, “I’m in a happy relationship today, and I’m committed to helping others professionally and personally. Other survivors are not doing so well. Many have addictions, mental health problems, cannot work. There was no help in coming to terms, pastoral care or financial compensation. Until now.

Babies who were not perfect went to another wing

The fact that the – long expected and yet critically received – 2021 Commission Report, which includes witness statements, documents, reports from the homes, autopsy results and scientific and historical research, was followed by an offer of compensation seems positive at first glance. But only the mothers get money – between 5,000 and 65,000 Euro, depending on the length of stay in the institution. The condition that they must have spent at least six months in a Mother-and-Baby-Home in order to also be entitled to compensation themselves has left the surviving children “devastated”.

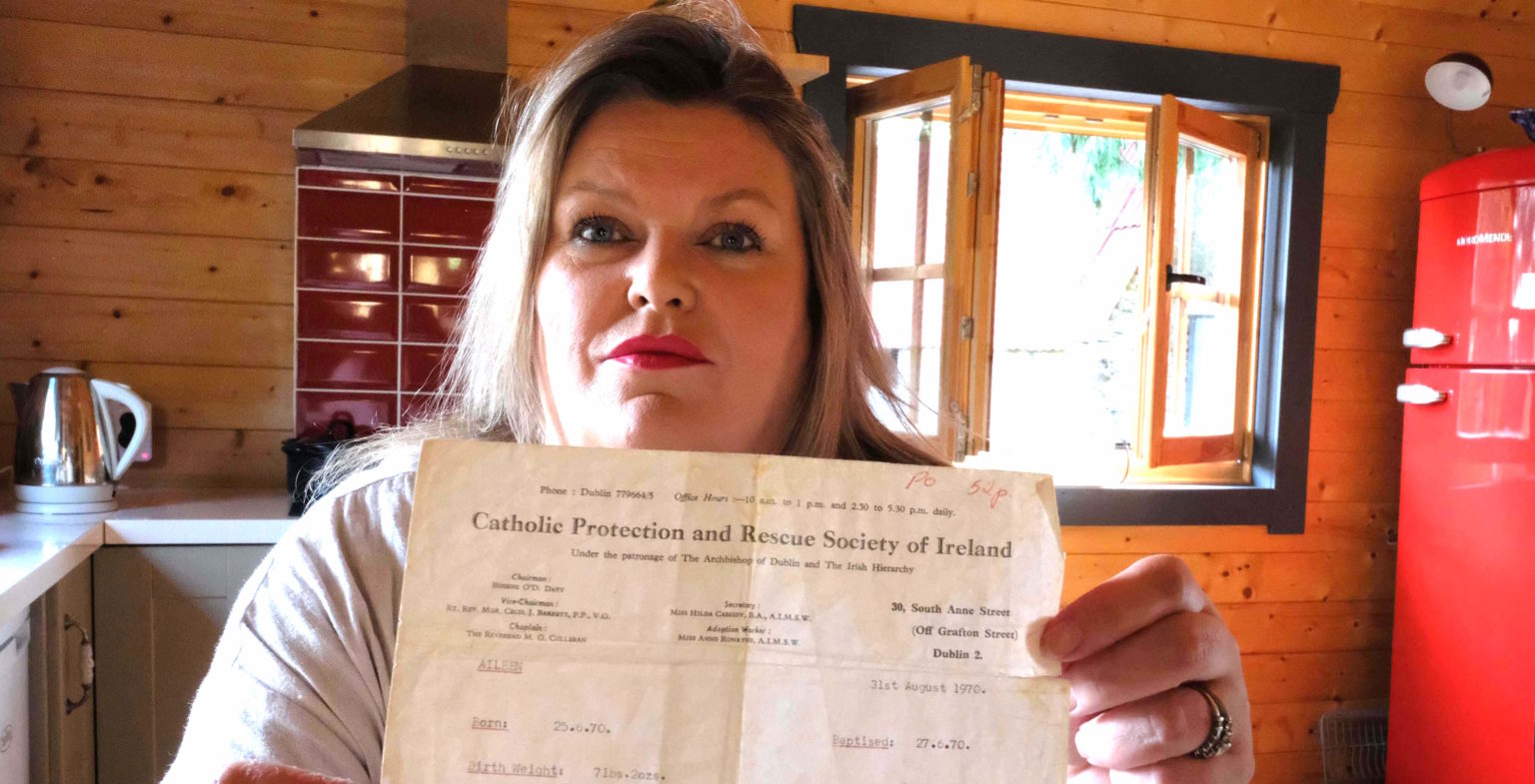

“We’re back to square one,” says 51-year-old Clodagh Malone, who was born Aileen in St. Patrick’s Mother and Baby Home in Dublin and who founded the self-help and search organisation Beyond Adoption. In a box on her kitchen table is an unbound advance copy of the commission’s report. “The Government knows that many of the survivors will not be alive in a few years. Some of them were hoping to get a few Euro to afford their own funerals. I am trembling with anger.”

Clodagh Malone recalls how babies fared in the homes, whether they were there for a few weeks, months or years. “Many babies who couldn’t be given away quickly were extremely neglected, left in cots 23 hours a day, rarely changed and bottle-fed while lying down. Especially the children who were not ‘perfect’, had a disability or were of mixed race. They were put in another wing of the building and pretty much forgotten,” says Clodagh Malone.

She reports memories of the young mothers who observed how “many of us were used for medical experiments and vaccination tests”. Some were given goat’s milk instead of infant milk. She herself is still very sensitive about nutrition to this day, she says as she puts bread and a plate of cold cuts on the table. The women and men in the self-help groups report psychological and physical consequences, addictions, and digestive problems.

Pope cancels mortal sin in Ireland in 2018, hotlines inundated with calls

“I am one of those who was still lucky – even with my adoptive family – but I have nightmares, a cleaning compulsion, health restrictions and, like many of the adopted children, a great longing to know where I came from.” She knows the woman who gave birth to her, but does not have a close relationship with her. Many, Clodagh Malone said, who have not been able to find their mothers (and fathers) to this day, look for clues in everyone: “Could I be related to this person or that one? Most have all their documents with them at all times – like Paddington Bear.”

Until a few years ago, the Church told many Irish women – despite the harsh treatment of them by many devout Christians – that it was a mortal sin to seek their children taken away through forced adoption. In a personal conversation with Pope Francis during his visit to Dublin in August 2018, Clodagh Malone asked him to say clearly that women should be allowed to seek their children and children should be allowed to seek their mothers.

The next day, at the closing Mass broadcast live on Irish television, the Pope announced: “We ask forgiveness for those children who were taken away from their mothers and for all those times when so many single mothers who tried to find their children that had been taken away, or those children who tried to find their mothers, were told that this was a mortal sin. It is not a mortal sin.” Within seconds, the phones of the aid agencies and adoption centres were inundated with calls.

However, finding the children again was virtually impossible for a long time, even for the mothers who were not afraid of committing a mortal sin – because of missing documents, cover-up attempts that were difficult to prove, forged signatures or by parents of underage mothers who had agreed to the adoption, changed names, and because DNA-based research was only possible at a late stage. Some children were passed out of the window at night without papers, even before adoption was legalised in Ireland in 1952. Many were sold to America.

Clodagh Malone explains: “It was an adoption machine that got going.” It was not unusual for a priest to fly to the USA with five babies. The priest was seated in first class and the stewardesses took care of the babies. The pilot had champagne brought to the priest and the other passengers had applauded – “because he was bringing such beautiful, plump babies to new families in America“.

A car pulls up in front of Malone’s house and she begins to beam. The door to the kitchen flies open and her daughter and her daughter’s boyfriend come in. “I have three children, two grandchildren and a great husband.” She hasn’t been part of the Catholic Church for a long time. Although she is very spiritual, she no longer wants to support this institution. And Maggie Corbett adds: “Why I haven’t lost my mind? I always told myself: You can create human life with your body. This is a miracle. You are a miracle.”

PODCAST TIP:

A look at other countries: Between 1956 and 1984, thousands of unmarried pregnant women in the Netherlands were forced to give their babies away. The podcast “Separated by force” by our Netherlands correspondent Sarah Tekath uncovers this dark chapter of Dutch history by listening to both the women’s and the children’s experiences. In addition, legal experts and historians explain the social situation during this time to draw attention to the injustice done to Dutch women and their children for decades. In one episode, the Irish women from this article also have their say.

Link: https://www.spreaker.com/show/separated-by-force