Two-thirds of the 2021 Irish Book Award nominees for crime fiction were women. A quota that is no surprise in Ireland. For years, the majority of thrillers, horror novels and psychological crime novels have been written by women. “We know more about fear than men do,” says last year’s winner Catherine Ryan Howard.

By Mareike Graepel, Dublin

Catherine Ryan Howard and Liz Nugent have killed 31 people between them. Yet they seem friendly, relaxed and not at all cruel as they sit on the patio behind Nugent’s pretty terraced house. Maybe a little hungry, okay, but it’s lunchtime. Liz Nugent fetches antipasti, dips, bread and cutlery. Not just the knife on the table is dangerously sharp, but the imagination of them both: They are among the most successful crime novelists in Ireland.

If we add the victims of Sam Blake, Tana French, Jo Spain, Sinéad Crowley and their colleagues, the total number of dead runs into the hundreds – but every single victim is “only” one on paper, because none of the authors has been guilty of murder in real life. But they all know the fear that something could happen to them – especially when they are out alone in the evening or at night.

According to a survey by the Fundamental Rights Agency, Ireland has the second highest number of women in the EU who avoid places or situations for fear of assault: Nine out of ten feel uncomfortable when they are out alone and yet there is a real danger: Almost 15 percent of Irish adults have been raped at some point in their lives, according to a recent study, and one in three has experienced some form of sexual violence.

“I always keep my key in my hand as a potential weapon when I’m walking home in the dark, and I only walk along busy roads,” explains Liz Nugent, who has won several Irish book awards and the prestigious James Joyce Medal in recent years. Her latest crime novel is called “Our Little Cruelties” and has just been published in Germany. “My husband always takes the shortest route home from the train, through the park. I never do. What’s it like to walk through there alone? No idea.”

Characters do not have to be likeable

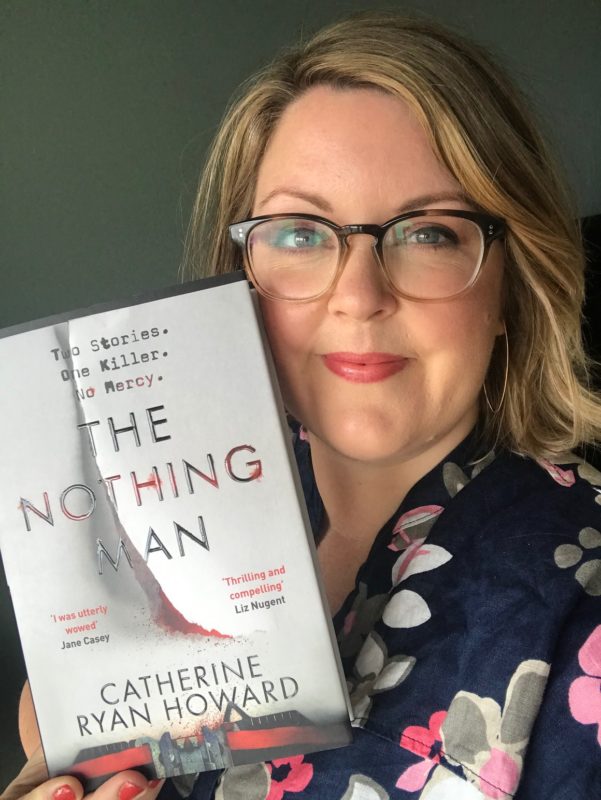

Catherine Ryan Howard, who turns the tables in “The Nothing Man”, and lets one of the female victims escape to try to hunt down the serial killer, describes waiting for the local Dublin DART train like this: “I ask myself every evening at the platform, next to which person will I be safest? Where do I stand? At least white, heterosexual men don’t perceive fear the way we do. Men write of macho heroes; women often write from the point of view of the stalked.”

Which does not mean that there are no men in their books. Or that they are exclusively perpetrators. But Catherine Ryan Howard is careful when fleshing out the male characters not to ascribe too much empathic capacity to them. And Liz Nugent is careful not to let the men be too observant. “Noticing bodies, clothes and physical details and describing and evaluating them in others – especially women – is not something men do,” she says.

The gender ratio of her readers is very different. Liz Nugent knows that 60 percent of her readers are women, while Catherine Ryan Howard’s crime novels are read by about 80 percent women. This may be due to the main characters. In fact, in Liz Nugent’s books it is very often from the male characters’ point of view that the Dubliner writes.

The three brothers in her current crime novel, for example, are each difficult in their own way, egocentric types in show business. They are characters who are not necessarily meant to be sympathetic to the reader, but who fascinate nonetheless. In its review of the book, the weekly DIE ZEIT writes that it would be a euphemism “to describe the internal relationships as dysfunctional: Toxic would be a better description.”

Liz Nugent says dryly: “I like to write fiction from the male perspective. Men don’t plan so far in advance – which suits me fine, because sometimes when I’m writing I don’t know what the resolution of the crime will be in the end. And men are more straightforward in their thinking, they don’t doubt themselves so much. This is another reason, says Liz Nugent, why it is all the more important to celebrate the success of women in the crime genre. In her opinion, Irish women have – finally – found their voice and no longer need to be quiet.

Women free themselves

But why is the big success only coming now? Women being afraid is not a phenomenon of the new millennium. Even in Bram Stoker’s time, the inventor of Dracula, they were most likely reluctant to walk alone at night – and not just because they were afraid of vampires. Nevertheless, until recently, there were fewer successful female crime writers in Ireland such as there are at present.

Valerie Bistany, director of the Irish Writers Centre, puts the trend in chronological order: “Crime and thrillers by women have been very popular in Ireland for about a decade, when Tana French started the wave and had international success with her first novel ‘Into the Woods’. “Some Tana French thrillers have been turned into a TV series called “Dublin Murders”; Liz Nugent’s books have already been translated into 15 languages.”

Nugent herself backs up the explanation of the trend with historical and legal changes: “Women in Ireland, thanks to the vice the Catholic Church put on society for a long time, had hardly any rights and no voice until the 1990s. Divorce, contraception, homosexuality and abortion – these were all illegal.”

Ireland voted for same-sex marriage as recently as 2015 and for abortion rights in 2017. There are currently many innovations in many areas of life in Ireland. For well over a year now, a shocking report about Mother and Baby homes and forced adoptions has been preoccupying the country. “When will this finally stop, that we have to read such news? It’s time we listened to women: in real life, in literature, everywhere,” says the successful author.

“Women often write in stolen time”

In another interview, Sam Blake has another explanation for the success of Irish female crime writers, which she also links to a social change: “In Ireland, we do have a long tradition of the macabre and the criminal. Even Sherlock Holmes inventor Conan Doyle was of Irish descent and spent a lot of time in Ireland as a child. The fact that there are so many female thriller writers now also has to do with modern technology and the new generation of women. But many of us still manage to do it mainly through hard work – often writing in stolen time, even though we work during the day, look after the family and run a household.”

For Catherine Ryan Howard, writing is now a full-time job – “56 Days” is her fifth book – and she is grateful for it. In order to be able to do this interview, she made a big exception by taking half a day away from her desk, where she is currently writing her sixth crime novel. “I really don’t do that in the writing phase normally. I disappear, but I let my friends and relatives know beforehand. That way I can retreat for weeks and write.”

She explains that she is often inspired by news stories and builds her plot on a bizarre fact or crime she stumbled across in the paper. Sometimes, she says, it is public and anonymous confessions on websites such as postsecret.com that can form the basis for a crime novel. “I find unsolved cases or loopholes in laws particularly exciting, so I don’t let up until I find a way to solve the case in my fictional version of events. I determine very precisely what the plot should be before I start writing.”

Liz Nugent works differently: “Sometimes I don’t know how the story is going to end until I have written two-thirds of the book. Writing is also very exciting for me.” She pours some tea for everyone at the table and continues: “I write so that I don’t get lonely. When I write, I am surrounded by my characters. The darker I let their characters become, the more I gossip and curse about each other’s characters in my head like at a coffee gossip party.”

Both can make a living from writing today. But that was not always the case. 39-year-old Ryan Howard worked as an administrative assistant for a travel company in The Netherlands and as a receptionist at a hotel in Disney World, Florida. On her website, she reveals that she used to be obsessed with the idea of becoming a virologist and that she still hopes to be an astronaut for NASA when she grows up.

Liz Nugent, born in 1967, used to tour as a stage manager with “Riverdance” and work in administration at the public service television station RTÉ before writing her first plays for the Irish language channel TG4 and children’s television. Their jobs were as harmless as the sunshine in this Dublin garden – before they started murdering. On paper.